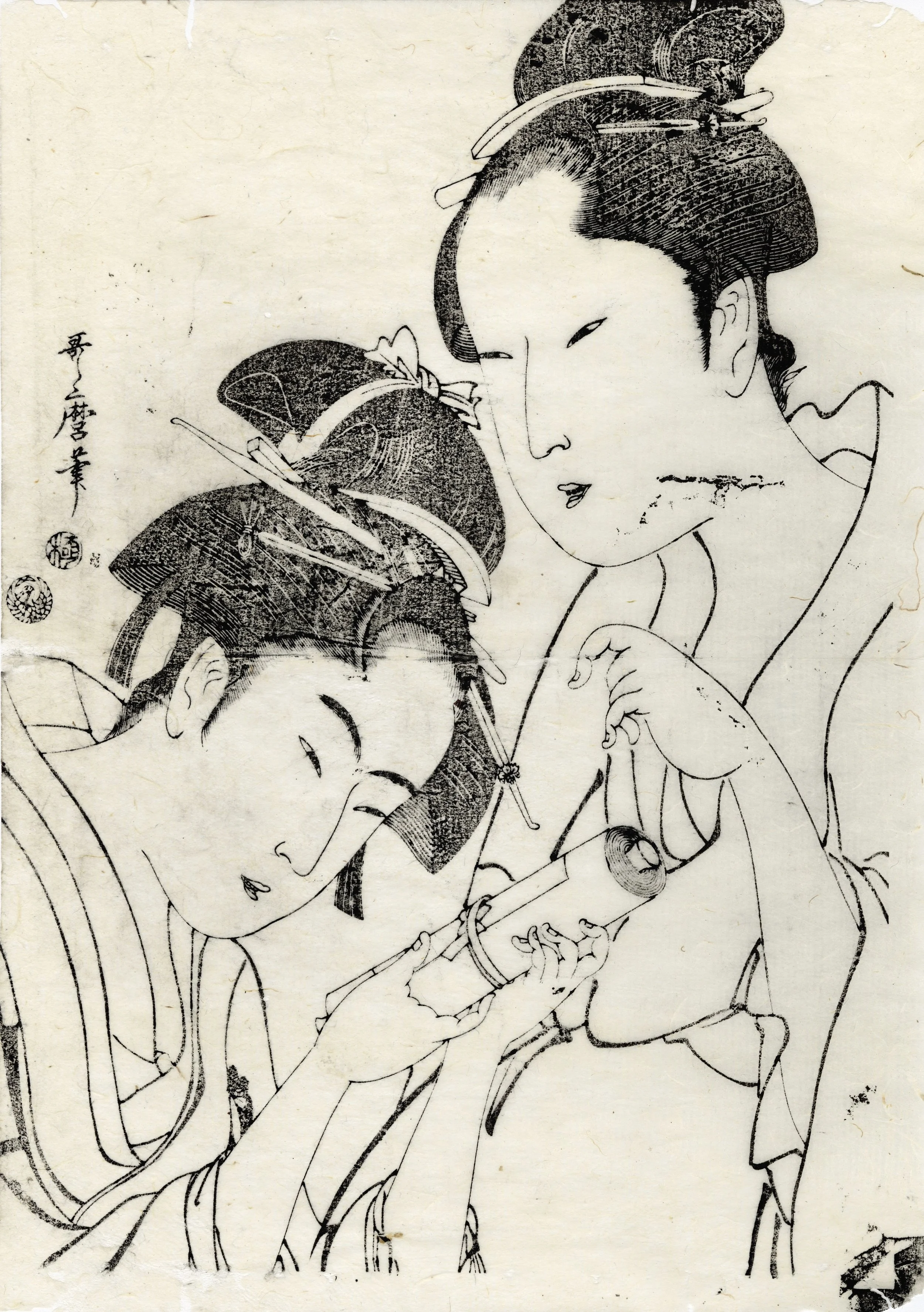

Kitagawa Utamaro (1753-1806)

Is there a line more elegant, more evocative, more sensual than the subtle curve that magically evokes the face or figure of a beautiful woman as drawn by Kitagawa Utamaro?

She can be a concubine or a mother or anything in between, in an elaborate kimono or a casual yukata with a glimpse of exposed breast, yet in this master’s hands, her every emotion and mood is captured with a smooth simplicity never equaled.

In all of Ukiyoe, Utamaro was the undisputed master of the beautiful woman -- or bijin -- print, and his works in and of themselves constitute a golden age of the Japanese woodblock art. He was born in 1753, just as the form came into its own, and died in 1806.

He first produced actor prints in the style of Shunsho, but quickly adjusted his focus to beautiful women in the style of Kiyonaga. He mastered both face and full-figure portraits – always slender and graceful -- and showed a sly talent for erotic prints: his are often sexy without being overly explicate. He also produced dozens of books and was something of a lively character in the great Edo social whirl of those days, known around town for his personality, joie de vivre and charm as much as for his talent.

In all he worked with about 60 publishers. He could capture a woman’s complex emotions simply by the angle of her almond-shaped eyes or the ripe shape of her slightly parsed lips. So many of these women seem as if from a dream, and as if they are lost in their own dreams; they appear to be simultaneously of this world and from another one that we mere mortals cannot begin to imagine.

And whereas sometimes having small children in Ukiyoe brings down a design’s value, in the case of Utamaro, who produced many, many prints of mothers and children, the opposite seems to be true.

He established his own school. In due time, as Ukiyoe became more and more colorful and, perhaps, decadent, Utamaro fell from favor. Late in his life he was briefly imprisoned for a print depicting the Hideyoshi Shogun with courtesans.

But his reputation grew to spectacular heights as the West discovered Japanese woodblock prints in the late 1800s and early 1900s.

Partial citation: Highly Important Japanese Prints, Illustrated Books and Drawings, from the HENRI VEVER Collection: Part 1 (Sotheby & Co.; 1974). Marks, Andreas, Japanese Woodblock Prints, Artists, Publishers and Masterworks: 1680-1900 (Tuttle; 2010).